|

|

|

Search our site

Check these out    Do you have an entertaining or useful blog or personal website? If you'd like to see it listed here, send the URL to leon@pawneerock.org. AnnouncementsGive us your Pawnee Rock news, and we'll spread the word. |

Too Long in the WindWarning: The following contains opinions and ideas. Some memories may be accurate. -- Leon Unruh July 2006Storehouse of lost thoughts

[July 31] I came across this photo of a granary that sat on the farm of my Unruh grandparents, Otis and Lena. It's a bland building that was easily dismissed from memory two minutes after you saw it. But things like this are never really forgotten. This granary was built of pine 1x4s and 2x4s in the 1920s or '30s. It rested on a few concrete blocks on the north side of the farmyard, close to the shelter belt. I photographed it in the mid-1970s for a book I was making for Grandma's birthday. The granary had thistly weeds on three sides. We grandkids built tunnels in them for several summers, on the east side between the granary and the garage. We were safe from the geese there. The old white-painted single-car garage smelled of grease. Cousin Mary brought her friends to the farm; one time I pushed Clara Anderson down into the weeds because I had a crush on her. The granary was next to the farm's fuel tank, which was mounted on a tall wooden frame. The fuel filter's sediment bottle glowed when the sun shined through it. The ground beneath the hose was permanently dead. The old tractors chug-chugged to the tank. A big hill of red ants lived at the base. The granary had rats. I used to set traps for them -- leg-hold spring traps suitable for rabbits. One crisp afternoon with a low-angled sun, Grandma -- dressed in a jean jacket, scarf, and dress -- helped me corner a rat in a yellow auger behind the granary. A few times I hunted them with my yellow fiberglass bow, but that never worked out well. It was fun, though. The granary had a small door above the main door so that the auger could pile the wheat high. A series of slats fit across the inside of the main door to keep the grain from spilling out when the door was opened. I saw Grandpa put grain in here a few times. When the grain was removed into trucks to be carried to a drill, Grandpa or Uncle Laramie stood inside and shoveled it out into the base of the auger. Grandma said there was mercury on the wheat and we should never climb in there. The granary was not far from the chicken house and a smaller henhouse. The henhouse always was overgrown with weeds and, like the granary, never was painted. The henhouse was dusty beyond belief and stank of ammonia and was crowded with buckets and other stuff that a farmer never throws a way. The granary was replaced, for all useful purposes, by a galvanized metal granary along the driveway. The granary was dismantled after the farm was sold to pay for Grandma's care at the nursing home in Great Bend. The granary . . . when I start walking down Memory Lane, I might as well take all afternoon. The call of the lawn[July 30] As I drove home from work Saturday evening, I passed a fellow sitting on the grass in his yard. It took a second before I realized that he wasn't relaxing; he was yakking on a cell phone. Isn't it enough that people talk into those phones at the grocery store, at the office, and behind the wheel? If there's one place that should be too sacred for a cell phone, it's a lawn. Your family and mine -- and maybe it's the same for that fellow with the phone -- spend a lot of time and money turning our property into land worthy of a park. So why is it so hard for us to sit back and enjoy that yard? When I plop myself down into an Adirondack chair, the boys come up and invite me into their games. Or my wife, sensing a vacuum in the workload, guilt-trips me into doing the dishes or picking up stuff or pulling weeds. Back when I was kid in Pawnee Rock, in the shiny days, our family bought a couple of lawn chairs. They had soft plastic tubular webbing, unlike the lower-cost flat and scratchy webbing. Oh, I loved to lie back on that green and white chair and listen to the insects and birds. One of Dad's rewards for a day of work was sitting on the front porch steps. His parents sat in their porch swing. My mom's folks sat in their hickory-grove patio or in their screened-in back porch. They sat and they talked, or they didn't talk. But they listened. It used to be that when one walked or drove around Pawnee Rock in the evening, you'd see lots of folks sitting out front. You'd wave, and they'd wave back. Shortly after the fireflies came out, everybody would agree it was getting a little dark and maybe it was time to go in now. I don't see many people relaxing in the yard these days. Maybe they're inside on the computer, not that there's anything wrong with that. Or they're watching television or driving the kids somewhere or working a just few extra hours this week. Or, like that fellow sitting in the grass, they're keeping in touch with someone somewhere else. Perhaps some people are afraid to be alone. Newspapers last week carried a report saying that people often most regret not the things they did but the things they didn't do, the pleasures they turned aside. Well, here's a simple pleasure: Leave your phone inside and sit down in a lawn chair. It's our world, I say, and let's relax and enjoy it. I'm going to start today, unless my wife needs something done. Mennonite rebels[July 28] No doubt you've heard about Floyd Landis, the American cyclist who heroically won the Tour de France this month. Or didn't win it, depending on a drug test. You may have also heard that he grew up a Mennonite in Pennsylvania but, against his strict parents' wishes, took up bicycle racing. Who would believe that a Mennonite kid would ever do such a thing? And Floyd -- he of the pure country name -- is known to have a drink or two as well. I imagine that all Mennonite kids are a little rebellious, and I say that because our group of kids in Pawnee Rock was that way. The Bergthal Mennonite Church had a youth program called Christian Endeavor, or CE, and it met on Sunday nights at the church. I had my first beer after CE. I was 15 or 16, and it was in the back of an older kid's car on a winter night. All six of us took a sip or two of Coors, and if we didn't like it, we pronounced it "green." As in not really drinkable. As if we would know. As if it mattered with Coors. That was in the days when Coors was marketed as a somewhat prissy beer, trucked only in refrigerated trailers and not available east of Kansas. It was easy to make excuses for Coors. Mistreat your Coors, the myth went, and it could go green on you. It was perfect for semi-rebels. Later, some of the kids later did develop a taste for drinking, but that was in the days when age 18 was legal. Anyway, beer drinking is a Mennonite tradition. You knew that the Mennonites were renowned for their brewing in old Russia, didn't you? Did you think all that Turkey Red wheat was grown just for bread? Apparently someone lost the beer recipe on the long trip to Kansas. I bet a lot of one-time semi-rebellious Mennonite kids are cheering for Floyd Landis. Overloaded with testosterone or not, he did in the Alps what every one of us has pretended to do when we pumped our way up the hill by the Rock -- and he did it in tight black shorts. The night light[July 27] Grandma Unruh used to do us kids a big favor -- she let us sleep in her yard. We spread a couple of blankets on the short brown grass, put our pillows at one end, and covered ourselves up with a sheet or another blanket. Our preferred spot was about 20 feet from everything: the two-story farmhouse, the root cellar, the shed, the elm and locust trees, and the wire fence. Once Grandma turned off the yard light, there was nothing between us and the Milky Way. The July wind went to sleep shortly after dark, most nights. The nights were quiet, but "quiet" is misleading. The darkness was full of adventure, if you only kept your eyes and ears open. Every sound was clear: Dogs barking a couple of miles off in any direction. The hog feeders clanging at Durward and Mickey Smith's farm, a half-mile away. Cicadas. Trains. Trucks gearing down near Pawnee Rock. Leaves rustling in the trees, sounding like soft rain. Teenagers racing their engines on the road past the cemetery. Planes four miles up blinked their way across the constellations, and meteors flashed and expired. The grand prize to spot was a satellite, and this was close to the days of Mercury and Gemini, when all of space was still a wonder. One night there was a tremendous glow. I walked around to the side of the house to see whether a car was coming. Men who killed in cold blood and dangerous walkaways from Larned State Hospital made the news, and I just knew that some night one would steal a car and come down the driveway. There weren't any headlights this time, and there weren't any UFOs (my second greatest fear). I figured out years later that it was the northern lights. To tell the truth, the murderers and UFOs weren't my biggest fears; they were just the ones I could express to myself. Grandpa had died in the farmhouse a few years earlier, my first family member to go, and I had bad dreams and sometimes night terrors. Lying on the grass with the other kids was comforting. With them at my side, I could look into the vast night until my imagination wore itself out. The stars provided enough brightness that I could see all the farmyard and fields in shades of gray. It became obvious over time that night was just like day without as much light. I know that sounds less than profound. But the trick to understanding the night was to not demand brightness; to see at the darkest hour, I only had to accept the light that was there. Friends of Pawnee Rock[July 26] Several regular users of the site have asked for help getting in touch with people who live or used to live in Pawnee Rock. Because this site is meant to help keep our Pawnee Rock connections alive, I'm setting up an e-mail directory that will make it easier for us to reach one another. I've started a Friends of Pawnee Rock page. As Pawnee Rockers and former Pawnee Rockers send in their names, I'll add to it. Here's how it will work: 1. Send your e-mail address to leon@pawneerock.org and tell me you want to be listed. 2. Include as much of this information as you'd like: 3. To frustrate spam robots, I'll modify all the e-mail addresses. For example, leon@pawneerock.org will be listed at PR-leon@pawneerock.org. So, when you want to send an e-mail to anyone on the list, start with the address that's listed but leave off the "PR-" at the beginning. In other words, change PR-leon@pawneerock.org to leon@pawneerock.org. Let's give this a whirl. I think it'll be fun. The new boys of summer[July 25] My dad never was a star athlete, but he liked baseball. He and his friends played when he was in high school. It's the only sport that made him smile when he talked about it. Pawnee Rock once had town teams and Little League baseball, but enthusiasm dwindled out and the action moved to softball. Baseball thrived in Great Bend and Larned, especially during the years when Mitch Webster played American Legion ball for Larned. I wrote about him when I worked for the Larned Tiller and Toiler and the Hays Daily News, and I followed him when he went to the majors. Monday night, I got to see baseball through new eyes. I took our sons to a game between the Anchorage Glacier Pilots and the Athletes in Action Fire from North Pole. Grandstand admission cost $5 for me and $1 for each kid. It was Christmas in July promotion night; everyone got a Santa hat. These teams play in the Alaska Baseball League, which occasionally wins the National Baseball Congress tournament played each August in Wichita. Neither of Monday night's contestants will make that trip this year, however. ABL squads, their rosters filled by college players from the Lower 48, play real baseball. Pitchers pop the dust out of the catcher's mitt. The shortstops throw ropes to first. The batters use wood bats. Real baseball, with real sounds. I could see in Nik's eyes that he's ready to slug and throw. If I can teach him patience, he'll be pretty solid. Sam, I think, will absorb the math of baseball. They both loved the first-inning pop-up when the third baseman was knocked flat by the catcher. Playing even a few games will give them a storehouse of memories: the line drive snapping into the webbing, the cleanly fielded grounder, the glory of a solid hit, the bad hops, and the first time they're not called "easy out." Before long, my sons will be following games in New York and Kansas City, Chicago and Seattle, Anchorage and Fairbanks. Like their parents and grandparents, they'll know batting averages and pitchers' records. Maybe they'll even tuck a radio next to their pillow and listen to West Coast games when they're supposed to be asleep -- just as I did. The game will go on for another generation. When the boys talked about Monday's game, they were smiling. Roast pork

The Slaviks' hog shed burned one winter night. [July 24] Boy Scouts can lead a kid in directions he never thought he'd go. One night our troop was camping along the Arkansas River, nestled back in the cottonwoods on the west side of the river not far from the Ash Creek Point. The eight of us had a nice fire going. I broiled a catfish in foil and shared it with my friends. And then our scoutmaster, Ron Stark, strolled up with a frying pan and a bag of goodies. He heated some butter and rolled the meat in flour, and then the frying began. Soon we had a plate full of olive-size mountain oysters, hog style. Ron explained that they were a gift from the Slaviks, who raised pigs a half-mile west of the Pawnee Rock Bridge. Just a couple of us tried the oysters. They were tasty -- but keep in mind that anything cooked outdoors on a cool evening will be at its most desirable. A couple of oysters were left on the plate when the dining was done. It turns out that catfish will eat them too, as we found out later that night. That camping trip was among the last by our Scout troop, which disbanded not long after the high school was closed. And in the mid-1970s, the Slaviks' hog shed caught fire. Despite the efforts of the fire department -- old hay in a corrugated shed burns quickly -- the hog operation burned to the mud. Maybe anyone who eats beef, pork, or chicken from a neighbor's farm feels an attachment to that farm and family. All I can say is that I always felt a kinship with Dale and Linda Slavik after that oyster picnic. Expressing that to the Slaviks, however, is something that even Boy Scouts didn't prepare me for. Landmarks[July 23] We all know our home country: gently rolling hills in the north, flat and sandy lands in along the Arkansas River. Pawnee Rock, the park, is a bluff sticking out of the sandstone and limestone hills. Long revered as the zenith of our landscape, especially before it was torn apart to build the town, the Rock stands more than 60 feet over the town yet doesn't quite reach the altitude of the top of the Farmers Grain elevator, which stands more than 100 feet tall. That's how it is in central Kansas. When we look for landmarks, we're most likely to focus on white shafts rising above a cluster of trees. Our understanding of where we are is often determined by which elevators we see. It certainly solves the problem of having a carload of kids ask when we'll be there -- parents can point to an elevator and say, "When we get to that elevator, we're there." Over the decades, many vacationing Pawnee Rockers have headed up to Hays, then west on I-70 to the Colorado mountains. It's a daylong drive that passes a lot of pasture and off-to-the-side elevators. Frankly, it's a route so plain that even staunch defenders of Kansas' subtle beauty begin to look forward to the World's Largest Prairie Dog in Oakley. As the air gets thinner, the grass gets browner, and the trees get more lonesome, the atmosphere in the car gets perkier. We scan the horizon, all hoping to be the first to find The Mountains. Finally, Pikes Peak materializes out of the haze, nearly a hundred miles to the southwest. For some of us, Pikes Peak, reaching 14,000 feet, was our first big landmark. Pikes Peak is well known nationally, even moreso than our Pawnee Rock. And unlike an an elevator made of steel and concrete and paint, the mountain is a true land mark, made of stone and dirt rising thousands of feet above the fruited plain. Pikes Peak signals to us that we're coming to a different landscape -- the shore to the sea of grasses in which our beloved Pawnee Rock is just an island. Kansas Territory, as you probably know, once included Colorado as far west as the mountains. The city of Denver is named after a governor of Kansas. And as far as I'm concerned, a Pawnee Rock native can lay claim to Pikes Peak. Forty years ago, PRHS graduate Don Lakin was a cross-country runner at Fort Hays State University, where he was an All-American in 1963, 1964, and 1965. One of his races was the Pikes Peak marathon, which starts at 6,300 feet and goes to the peak and back down. I don't know whether this happened the year he won the 26-mile race (1964), but as his mom told it, he was dashing along when he lost a shoe, a sock, the other shoe, and the other sock -- and he kept running. I dare you to be tougher than that. A break in the weather[July 21] The heat wave was fun while it lasted, wasn't it? But all good things must come to an end. A lot of Kansas is going to be 20 degrees cooler today than it was Thursday. Too bad. When the "heat emergency" goes away, you have to start minding your manners again. Here are the high temps and high wind speeds for the past five days, measured at the Great Bend airport. Sunday: 104 degrees, gusts to 23 I imagine a lot of Pawnee Rockers are just tired of the brow-beating, energy-sapping, it-costs-a-lot-to-air-condition-this-house heat. I would feel the same way if it were my skin getting blistered every time I touched a car hood. Still, people who move from Kansas to near the ocean often miss the heat, that sensation of being thoroughly warm. I'm one of them. As much as I wish I could be toasted, I also wish for the antidote: a cherry slush from Dairy Queen. Sometimes Kansans find a friend in odd places. Here's a refreshing voice from England, suggested by sister Cheryl in Emporia. The weatherman's moment of truth[July 20] One of my many professions as an adolescent was weatherman. This was back when there was still magic in being able to tell what weather was coming by looking at the sky and feeling the air. I had my Pocket book of weather, my Scout handbook, and a few real maps mailed by a generous forecaster at the Dodge City weather station. By spreading the maps out on the floor of the dress shop (just west of the post office) where Mom was working at the time, I learned the arcane symbols for wind speeds and precipitation. My favorite tool, however, was a barometer I made out of tin can open on one end, a balloon, a rubber band, a straw, a bit of glue, and a piece of cardboard marked in increments. The balloon was stretched over the open end of the can and held fast with the rubber band, and then the straw was glued onto the balloon so that most of the straw hung over one edge of the can. It looked like something out of a Cappy Dick manual. The idea behind it was that as the air pressure decreased, the air inside the can would expand, trying to fill the vacuum in nature. That forced the balloon outward, pushing the pointer end of the straw downward relative to the markings on the cardboard set up beside it. As a high-pressure system arrived, the balloon would cave downward and the pointer would rise. The Unruh Weather Service -- I tried on a lot of businesses in those days -- offered its forecasts to the public. My parents were solid customers, but I suspect that they were just being kind. Still, for all my background in forecasting, I'm a sucker for heat lightning. Back in the 1980s, I drove from Wichita to Kanopolis Reservoir for a summer night of camping. Maybe I had drunk too much iced tea, but I just couldn't settle down. After dark, I found I still hadn't set up camp, so I drove to Salina, then back to the reservoir. I parked on a bluff overlooking the lake. The lake, as it is now, was very low. The air, as it is now, was very warm. But off in the southwest, lightning flashed, again and again and again. Was it going to rain? I thought maybe it would, although the light breeze brought only the aroma of dank lakebed. Within a couple of hours, I had myself convinced not only that was it going to rain, but also that the storm was likely to deliver tornadoes and hail. By 3 a.m. I was back in Wichita. Now, if I had just had the Internet with its 24-hour forecasts and radar, I would have known that this particular storm was just an electric conversation between dry ground and semidry clouds. And I probably would have stayed at the campground. But if you know everything, where's the magic? Standing too close to the sun[July 19] A real estate agent was showing a couple of folks around a farm yesterday in central Kansas. They stopped for a moment in the wispy shade of an locust tree. "Why," the agent said expansively, "all this farm needs is water and good people!" "Pshaw," said the wife. "That's all Hades needs." Speaking of places where a snowball doesn't have a chance: Pawnee Rock's official high temperature Sunday was 104 degrees. Monday, 105 degrees. Tuesday, 105 degrees. Today, it's forecast to be 107 degrees. But it's a dry heat; that's what you say when your head is too baked to think of anything clever. And if you somehow get sweaty, that 10 mph breeze will dry you off in no time flat. I hope someone in town will fry an egg on the sidewalk. Perk up! This is the kind of weather when legends are made! Staying indoors? Try these sitesDistance: Plot mileage for all sorts of trips at Gmap-Pedometer.com. Get the Google map centered where you want to start, then click on "start recording" on the left side of the screen. Then double-click on the map at the point where you want to start measuring, and double-click on waypoints until you get to your destination. The "pedometer" is flexible. You can measure the distance of a wayward cross-country trip or just how far it is to the post office. I use it for fun things such as figuring the exact distance from my old house to Ash Creek Point (3.7436 miles, give or take a couple of yards). Temperature: Want to follow the heat, wind, and humidity in Pawnee Rock/Great Bend? Pawnee Rock's official weather data are gathered at the Great Bend airport, 8.7 miles (as the southwest wind blows) from downtown Pawnee Rock. Go to this Weather Underground history page. Change the date to find information for different days. Flying with the farmers This is Fort Larned, along the Pawnee River (also known as Pawnee Creek), as seen from a Flying Farmers plane about 1975. The fort was built in the mid-1800s to protect travelers along the Santa Fe Trail near Pawnee Rock. [July 18] In the 1970s it seemed that wheat prices were so high that Kansas' farmers were harvesting real gold. And so a lot of farmers did the logical thing -- they bought airplanes. Farmers already had big flat fields and mowers, perfect for landing strips and maintaining them, and they had combine sheds that could easily be converted to hangars for Cessnas. Why did the farmers need planes? Well, there's that big game up in Hays next month, and Mabel's folks down in Oklahoma need a visit, and . . . frankly, a lot of farmers liked to brag that they had a plane. Many of them were members of the Flying Farmers organization, which now pushes for putting more airports close to town and has goals like "help reduce unnecessary regulations for general aviation" and "to insist that aviation gasoline taxes, where collected, be used for the development of aviation." But in the 1970s, Flying Farmers were beloved by youngsters and the adventurous because once or twice a year these fun-hearted pilots offered penny-a-pound flights for charity. Go to the Great Bend or Larned airports on those days, stand on a scale, pay your money, and get a bird's-eye view of your town or farm. A family of four could fly for less than $5, which was a bargain even when a dollar was still worth nearly a dollar. Once you get a taste of flying, it doesn't go away. More than a decade later, when I lived in Wichita, I found myself with the choice of buying flying lessons ($3,000) or making a down payment on a house next to a park along the Little Arkansas. (I chose the boring option.) But because some farmers chose to write checks for a Cessna 172 instead of a new combine, we got to take rides that never really ended. Where friends meet to eat[July 17] A few years ago during a visit to Pawnee Rock, my wife and I went with Dad and Betty to a hamburger feed in a churchyard. It was great to see friends and show off my wife, who most of the folks there had never met. Chattering happily, my wife and I moved through the food line and sat down with Maxlyn and Earl Schmidt. One bite later, all four of us realized that our charred hamburgers were cold pink on the inside. Back in Dallas, where we lived at the time, we would have raised a stink had our burgers been served with risky uncooked centers. But we weren't in Dallas anymore, Toto. The old guys at the grill were having a great night cooking and serving. It would have been ungracious to ask for a burger "cooked all the way through this time." So we kept on smiling and ate our chips and potato salad, and I gently collected the plates and quietly walked them over to the trash can under the big elm. To my surprise, there were a lot of half-raw hamburgers already there, and not a discouraging word had been spoken. It's nice to know there's still a place where people will overlook an inconvenience. I don't think they were there for the food anyway -- I think they really only wanted to sit in a grassy yard and chat as the day slipped into dusk. And that, my friends, is what makes a hometown. The beautiful bamboo rod

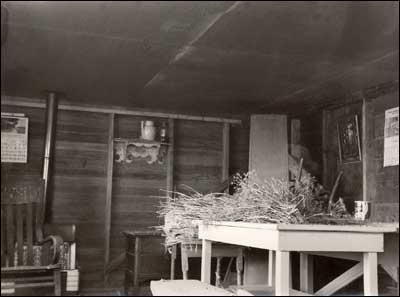

The brooder house on the Otis and Lena Unruh farm in the 1970s.

[July 16] The first thing was always the dill. Grandma dried her dill weed on the table, and the scent filled my nose as soon as I lifted the hook on the door and stepped inside the brooder house. The rocking chair was dusty, but it was big and well worn. The calendars were only a few years old, their scenery not yet faded. Pickle crocks squatted against a wall of unfinished 1x4 pine. Its days as a chicken hatchery over, the brooder house stood outside the fenced yard, between the round end of the driveway and the field. In some ways it was the guard shack for the farm, because the electric-fence charger was inside. "Bzzzz-thmp, bzzzz-thmp," the charger would say, sending its message out to the cattle. One window opened to the east and another to the south, on the long side of the building. I stood before the south window, surveying the dry-land wheat field like a gentleman farmer. The brooder house on the Otis and Lena Unruh farm was my playhouse, if 12-year-old boys are allowed to have playhouses. Along with my sister and cousins, I spent rainy days in there. On hot days, when everyone else loved the air conditioner in the farmhouse's dining room, I often went off by myself and read fishing books. Above the south window was the prize of the farm: Grandpa's split-bamboo fishing pole, lying on a row of nails pounded into the wall studs. Why, I wondered, would Grandpa have such a beautiful thing? He never told me about fishing (he died in the fall of my third-grade year), and neither Grandma nor their four offspring ever spoke of fly fishing. Grandpa didn't have a pond stocked with bass or bluegill, and we lived hundreds of miles from the nearest trout. Yet there it was, the honey-colored bamboo gleaming under the dust, the reel still wrapped with dark cotton line, the ferrules unrusted, the twirled wire guides held firm by thread and varnish. Perhaps the rod had been a gift to Grandpa on some long-past birthday, or perhaps it was a memento from a rare trip away from central Kansas. Maybe he bought it as a promise to himself that he would one day stand in a clear stream. I used the pole a few times as a teenager, but it was too graceful and unwieldy for the snag-filled waters I knew. I have a fly rod of my own now, a whippy graphite marvel that one evening landed a hundred grayling. When I stand in clear water and use my rod, I think back to the brooder house days. Am I doing, I wonder, what Grandpa wished he had done when he placed his fly rod on the nails above the south window and stepped back for one last look? That prairie hospitality, and so on[July 14] Pawnee Rock's hospitality is now known to the many Web fans of Scott Edwards, who is walking from Wisconsin to Arizona. Check out his Long Walk report. The camera in the sky is getting a better focus on the Pawnee Rock area. Our hometown has been in so-so focus for a long time in the Google Maps images, but now higher-resolution color images reveal the land as close as a mile north of town. Go to http://maps.google.com and type in "Pawnee Rock KS" to check out the gently rolling landscape. Of course, you can still find good ol' black-and-white images at Terraserver-USA.com. Thirty-five years ago, the Argonne Rebels Drum and Bugle Corps won the first of three consecutive national championships. This weekend, many members of the former corps are having a reunion in Great Bend leading up to the March of Champions competition Monday night. Pawnee Rock contributed to the Rebels' success: Dwight Dirks played a tympani, Laura Dirks a baritone bugle, and Andrew Stimatze and Leon Unruh soprano bugles. In addition, Kelley and Kris Underwood, two teenagers who went to grade school in Pawnee Rock before moving to Great Bend, played the bass drum and cymbals, respectively. (I've heard that Roger L. Unruh was in the corps in the 1960s.) The baritone bugle had the range of a trombone, and the soprano the range of a trumpet. The horns had one valve and one key -- an odd mixture but one that was easy to play while marching. And march and play we did, almost every day from March or April through Labor Day. After we won our first championship, in the Astrodome in Houston, the Highway Patrol gave us an escort from Oklahoma to downtown Great Bend. Thank goodness there was always Maxlyn Schmidt to keep us honest when we brought our exalted selves back to Pawnee Rock. She said it with a smile, but she said it anyway: The dumb and bungle corps. Shades of the past[July 13] Of the three large elms between the sidewalk and the street in front of our house, the westernmost tree was my favorite. It was 4 feet through and the one under which Dad parked his 1948 Chevy pickup. Its roots were thick and well defined, and one of them pushed up the sidewalk. Over the course of several summers in the 1960s, I created a pit between the first and second trees where I drove toy farm equipment and threw pebbles to knock down twigs stuck in piles of sand -- it was one of those little worlds where a kid can play all alone out in public. Grass never grew there; it was too shady. The second and third trees framed the gravel driveway. They were less dramatic, but they helped define the front of our property before the curb and gutter were poured. In the spring, the elms' saw-toothed leaves were large and bright. Suckers grew at the base of each tree, until I learned how to use a hatchet, and robins nested in the branches. In the fall, the leaves returned nutrients to the yard. Now those three trees are gone. Dutch elm disease got the blame, but it could also have been simple old age. The big branches fell or were trimmed off, leaving the trunks standing like Woodsmen of the World grave markers, and then the trunks too were cut away. Anybody who grew up in Pawnee Rock and comes back years later might sense an emptiness downtown. At first, that feeling might be attributed to the boarded-up windows or to the absence of familiar buildings. But that hot-in-summer, cold-in-winter hard appearance should bring up another thought: The big trees are gone. There used to be elms and cottonwoods in front of the Christian Church, the post office, the lumberyard, and Elgie's Craft Shop and at the corner near the old scale/Midget Malt Shop. Even the old nursery behind the Christian Church has been mostly cleared out. It must be acknowledged, of course, that the lumberyard and shop also are not there anymore. At one time, trees were loved and people openly loved the idea of trees. They were a symbol of settling the prairie as families set down roots of their own. Now, it seems, trees just get in the way. Some farmers, whose houses are protected by shelterbelts, rip out the trees so their crops won't have to compete for water. In town, you don't have to clean up leaves and branches if the trees go away. Are shady streets just a failing experiment? Is the loss of trees a subconscious effort to welcome the end-times or to bring back the dust bowl? Many of Pawnee Rock's trees were planted when the town was 100 people larger than it is today. What dreams did those folks have that led them to treasure their shade trees, their fruit trees, their elms under which little boys eventually would play? Building a door and going through it[July 12] My wife has taken our sons on a road trip to see whether they can help somehow with the rebuilding of a house on the TV show "Extreme Makeover: Home Edition." Eight-year-old Nik, who aspires to be an architect, especially hopes to get an autograph from the show's talkative hero, Ty Pennington. It's not a cheap trip, but my wife said that the boys don't often get a chance to brush up against big-time stars. (It seems that living with bears and moose and earthquakes isn't exciting enough for them.) She makes a good point, though. If we don't help the kids see the outside world when it practically falls in our lap, what good are we? In retrospect, it's amazing how much of the outside world we got to see in Barton County. Take the lyceum programs. Pawnee Rock schoolkids filled a few sections of bleachers every month or so for lyceums, an off-off-off-Broadway series of lectures. We had a couple of people who bicycled across Australia, for example, and a blind professional whistler who treated us to the theme song from the movie "The Bridge on the River Kwai," a couple whose trained miniature dogs entertained us for an hour, and a fellow who demonstrated closed-circuit television when that was still exotic. And opening each one of those doors to the outside world cost us only a quarter or two. Great Bend had the Community Concert series in the city auditorium. Our family had a subscription (season tickets) for a couple of years. Where else would we have seen Grammy-winning pianist Peter Nero, an opera, an orchestra, and Fred Waring and the Pennsylvanians? Barton County Community Junior College, as it was known at its creation, provided a wonderful series of lecturers and opened the doors to the public. In one year, I met astrologer Jeane Dixon, columnist Jack Anderson, and anthropologist Richard Leakey. And that's all because some people decided we in the dusty heart of the heartland should be exposed to ideas bigger than we might find in our own households. To the principals and civic leaders and college presidents who held the door open for us, thank you. You were right. Sixth grade, gone with the wind

Front row, from left: TaWanna Mason, Marla Johnson, Rhonda Countryman, Susan McFann, Jill Clawson, Ida Deckert and Brenda Schmidt. Back row, from left: Galen Hall, John Wright, Andrew Stimatze, Charles Moore, Todd Bright, Tim Barker, DeWayne Popp (later Davidson) and Rick Batchman. Kenneth Henderson must not have been there that day. [July 11] Where are they? These are my sixth-grade classmates, posing at a windy picnic on Pawnee Rock while I took the photo. That's Elva Jean Latas in the background; she was the hardest teacher in grade school, at least by reputation. So, where have they all gone? I made this photo in the spring of 1969. Three years later, we were getting ready for our sophomore year when Pawnee Rock High School was closed. Seven of the kids in this photo, plus me, went to Macksville, and the rest scattered to Great Bend and Otis-Bison. As far as I know, one of my classmates lives in Pawnee Rock, one in Larned, one in Great Bend, one around Dallas, and one near Seattle. It's my fault that I didn't keep up with everyone better. As I look into these faces, I remember a lot of the things we did together (learning the counties and county seats, for one). I think this is about the time we left the "wonder years" and starting forming serious cliques, which I guess is part of growing up. Most of us had been together since kindergarten. I'm cheered by seeing my old friends again in this photo, but saddened by the thought of what we lost by losing our school -- more precisely, what I lost by losing touch with these kids. The pump, the trees, the wax[July 10] Cheryl Unruh, the hard-working daughter of Pawnee Rock who now sets the world straight in Emporia, adds these to our list of what makes our town a hometown:

Cheryl's obviously wrong about the spinach; it was one of my favorite lunch items. But don't you remember working that red pump handle at the lumberyard, wanting water so much that you'd wake the town up with that screech? And the smell of fresh wax at school -- a whole new year of possibilities lay before us on the morning when we inhaled that scent. You can remember the janitors pushing their electric waxer up and down the hall, can't you? And the Methodist Church -- now a part of our history -- was always so friendly toward Scouts, 4-Hers and other organizations. Please -- add your thoughts about Pawnee Rock. Send one or a dozen; we have room for them all. Tell us what sticks in your mind about our favorite town. (If you'd like to get in touch with Cheryl, write to her at cheryl@flyoverpeople.net.)

12 little things about Pawnee Rock

[July 9] I was thinking about what I liked most about Pawnee Rock, and I found that quite a few things remained when the sorting was done. Here are a dozen things I miss about Pawnee Rock life: That's my list. What's on yours? A roof above our lives

The garage that once belonged to the Carpenters. [July 7] As a carpenter, Dad worked on a lot of houses in Pawnee Rock. He built our house and for other families installed cabinets, hung doors, painted walls, and did all sorts of hard labor in all kinds of weather. Although I helped him at the cemetery, where mistakes in mowing could grow back, I rarely got to swing a hammer with Dad on the job. Part of that may be because he did fine work and I often left circles around nails with that last whack. Dad understood wood and tools. He doesn't do carpentry anymore, at the age of 80, but some of his work of earlier decades endures. The one carpentry job he let me help with was shingling the Carpenters' house and garage. J.D. Carpenter had been a grocer for years, then must have been the town clerk, accepting utility bills paid in person at the city hall. He died in the late 1960s, I think, leaving his widow to live in a nice brick house just east of the New Jerusalem Church. It was a cool fall day about 35 years ago when Dad and I laid a new layer of green shingles atop the house. Dad carried bundles up the ladder and scampered around on the roof; it was the first time I had been invited up the ladder, so I lay as flat as possible at first to avoid tumbling into the shrubs. As the years passed, it gave me a great deal of pleasure to walk by Mrs. Carpenter's house and admire the south-facing roof where I had done most of my work. I liked the notion that I had helped shelter Mrs. Carpenter. Also, I could point to the spot where I had scraped a deep hole in my right hand while shoving a shingle into place. My badge of honor. Well, Dad is retired and Mrs. Carpenter is gone and the house has been torn out. A year ago, however, the garage remained, wearing at least two layers of green shingles. We all like to think we have contributed to our hometown. That roof is my last tangible hurrah, and I imagine its days are numbered. My hand, however, will bear its faint scar the rest of my life. We can cook[July 6] My mom is a pretty good cook, and adventurous too. She even had an international phase around 1970 (she's still liberal) and brought home a recipe for ground-nut stew, which basically is peanut-butter soup. Like many Pawnee Rock mothers, she had some recipes that she came back to when the budget was tight and the garden's vegetables were long gone. One recipe probably had a polite name in some high-dollar cookbook, but at our house it acquired the title "stuff." Stuff was a can of mushroom soup cooked with ground beef, onions, and rice. Maybe Mom and Dad and Cheryl liked stuff, but the texture of mushrooms didn't do anything for me. The fate of mushrooms in my diet was sealed when Mom lied about them on alternate days: "Eat them, you can't even taste them" and "Eat them, they taste good." Now that there are picky eaters at my own table, I understand what would lead her to say things like that. But I don't force the boys to eat mushrooms. Twenty or so years ago, an organization in Pawnee Rock raised money by selling cookbooks to which families had contributed their favorite recipes. When I looked at the book not too long ago, it struck me how so many of them included "Open a can of . . ." On the face of it, that doesn't sound like a very good recommendation for home cooking. But then I thought about it. If I had a personal cookbook, half of my recipes would include "Open a can of tomatoes . . ." The other half would start "Open a can of tomato sauce . . ." Apparently, I'm one can that didn't fall far from the shelf. Addendum: After seeing this entry, Mom wrote to expand my list of ingredients in stuff. She also noted that the polite term for the dish originated in the military and included the phrase "on a shingle." The tool talk[July 5] When I was a young fella, I had a carpenter's plane. My carpenter dad dropped it and it broke. I was very sad. Dad was working at the time in the telephone building on Bismark. He and I sat down on the front steps, and he told me about how his father-in-law, my grandpa, had broken one of Dad's tools when Grandpa came to help build our house. "And you didn't see me cry, did you?" Dad said. Yesterday I went bike riding with 8-year-old Nik. We were at a neighborhood grade school where a decade of kids have created a jump by riding down a hill, then into an 8-foot-deep ditch, then up and over a pile of dirt and rubber playground scraps. Nik went over it a few times, then goaded me to borrow his bike and do it. No problem. A while later, he wanted me to do it again, suggesting that I was a chicken. The lesson? That's why you wear a helmet. I pedaled hard and went way up in the air, the bike flying out from under me like on one of those broken-bones extreme sports shows. My head clubbed the dirt and I bruised my shoulder hard. Poor Nik's bike got scratched and scraped, and the front brakes were broken. After Nik went to bed last night, I gave him the broken-tool talk. He nodded and seemed a little thrilled about being the next in line in a multigeneration story. I'm sad to say, however, that the lesson might be one of those that doesn't really sink in until you are old enough to give it to your own kid. For now, I fall under the boys' current worst epithet: rockhead. But for two or three seconds, when the bike was running up the jump and flying, I was Icarus. A young, happy Icarus. Icarus the rockhead. Fireworks at midnight[July 4, part 2] We sat on the street in front of our house early this morning to watch the fireworks. The kids -- ours and a couple of their friends -- ran and skated on the sidewalk and street in front of us as the charges streaked up from Lions Park. Having the kids miss out on the show offended my sense of order. I told the boys to sit down and watch the show, but it was in vain. The Alaska sky was still bright at midnight (the fireworks started at 12:01 on the Fourth), and 8- and 10-year-olds won't be held back if you let them stay up to that hour. It occurred to me as the show went on that I had been the same kind of kid in the 1960s when our family piled into the Impala and went to Larned for the fireworks on the night of the Fourth. We ran up the hill at the ballpark and rolled down, ignoring the chiggers and being thrilled because we were playing at night under the floodlights and fireworks. Maybe the kids this morning weren't missing out on the fireworks show. In a kid's magical life, the fireworks are there to decorate the summer. The pyrotechnics over Eagle River this morning were a little over a mile away, six seconds elapsing between the burst and the arrival of the concussion. Six counts -- a lifetime between the flash and boom. History of fun[July 4] Pawnee Rock has a long history of partying on the prairie. The current thrills come from Pawnee Rockin Days, held the second weekend each August. The city throws itself a public picnic, a parade, and a street dance. There are still a few folks around who might remember back to the sepia-toned days when the Pawnee Rock state park was dedicated in 1912. A large crowd was entertained by speeches and a carnival on May 24. The "Biographical History of Barton County, Kansas" (published 1912) says: "The young people were afforded all kinds of entertainment. There was a Ferris wheel, a merry-go-round, a balloon ascension, a base ball game and dozens of other features to make the day one of fun and frolic." In the 1940s, there were parades with horse-drawn wagons and motorized vehicles. The highlight of the social season in at least the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s was the Saturday morning a week or two before Christmas when Santa rode down Main Street from Bismark Avenue on a firetruck. The truck stopped between the post office and the grocery store, and Santa handed kids dozens of paper lunch bags filled with oranges, nuts, and candy. There were squirrel-cage drawings for turkeys and hams. Santa's ride doesn't exist anymore, but the Christmas spirit continues with the city's angel tree. In the 1960s and 1970s, the downtown city park played host to dances and parties. Some organization or other held a turkey shoot at the salt plant; the best shooters won turkeys. Whichever bar was in existence in the 1980s -- Bob's or the Pawnee Inn -- had a July 4 pig feed. But here's something I didn't know until recently: Pawnee Rock had free outdoor movies in the 1940s. Pawnee Rock native Don Ross wrote: "If I remember correctly, picture show night was on Wednesday during the summer months. The show man would bring his equipment in on a small trailer, put his screen up on the north outside wall of the Lindas Lumber Co. This was before the tennis court was there, and the whole lot would be full of cars and even out on the streets. A lot of the city folks would park their cars early in the evening so as to get good parking. Most of the shows were cowboys, crooks and Indians. That's what we liked. "The show man would have intermission about halfway through, and we kids would all run over to the drugstore and get ice cream, pop and candy. Wow, those were the days. The business places in town paid for the shows and their commercials would be shown on the screen. Holmes auto repair, The Barber Shop, (merchants) J.L. Morris and J.D. Carpenter, Lindas, the drugstore and all the others. "Remember, this was before TV and it was a real treat for the folks of P.R." So, Pawnee Rockers, when you're downtown on a summer night and you sense happiness and laughter, don't be surprised. It's the ghosts of old Pawnee Rock coming around just for fun. Black and white and gray all over[July 3] Our first television was a Zenith. It appeared in the living room one afternoon in the early 1960s, a gray plastic box with rabbit ears. Things were different then. We soon moved the TV off the living room altar into the more appropriate family room in the basement, where it sat on a counter. Eventually we got an antenna on a pole outside my bedroom window, enabling us to pull in KCKT in Great Bend and KAYS in Hays. Dad didn't have much interest in the TV except on Sunday and Monday, and Cheryl and I often ate our Swanson dinners with him. No one touched the dial -- it was a dial -- when "Bonanza" and "Gunsmoke" were on. For all the bad things that have been said about TV and its effect on baby boomers, that little 17-inch screen took me places far from a green-painted basement in central Kansas. It took me into history: to Kennedy's funeral, to the war in Vietnam, to the riots in Watts, to the naming of General Curtis LeMay as George Wallace's running mate, to the Orange Bowl when Kansas lost 15-14, to the Watergate hearings and the resignation of Nixon. It took me into space: with Gemini, with Apollo, with Major Astro. It took me into fantasy and fun: "The Red Skelton Hour" ("Good night, and may God bless"), "The Monster That Challenged the World," "The Wizard of Oz," "Laugh-In," "The Andy Griffith Show," "Sea Hunt." It took me fishing: "This is Harold Ensley, the sportsman's friend, heading out in my red Ford Country Sedan." Now, when our sons want to watch TV, it's hard to tell them no every time. The shuttle Columbia broke apart over the city where Nik was born. 9/11 happened in Sam's second week of kindergarten. A lot of their friends have parents with time in Iraq. The world is out there, and they need to see it. And, of course, they're welcome to join me anytime to watch the Jayhawks. Fun and fear combined Cousins Mary Fox, Leon Unruh and Cheryl Unruh stand on Grandpa Otis Unruh's combine around 1962. [July 2] Farm kids may never know the rare pleasure we town kids had when we climbed on tractors and combines. For us, these red, orange, green and silver machines were frightening, alien, smelly, and exciting. Imagine being seven years old. You've climbed the three or four rungs straight up the side of the combine and you're standing on the platform, holding for dear life onto the wheel. In front of you sprawls the reel, underlaid with scissor teeth ready to shred you. Grandma said so, and you've watched while Grandpa tested the noisy teeth before moving into the northeast 40. In fact, the whole machine is noisy, much louder than anything in Pawnee Rock except the fire siren and the trains. The combine has a hard seat on a stiff piece of steel. Grease is tucked away in every corner. Because it's summer and the whole machine is hot, you can smell the gas, the oil, the metal, and the dust. The toolbox holds heavy tools and oily rags. The steering wheel sports a wooden ball, an object you'll later learn is called a suicide knob. By the way, if Grandpa gives you a ride on the tractor, don't slip off the back or you'll get plowed. And don't touch the PTO. You hope that Grandpa will let you ride the combine this summer, although you're kind of afraid that you'll fall into the reel or off the side. But you love to look into the bin when the combine is augering wheat into a truck; the grain gets sucked down and finally disappears. Don't fall in, Grandpa says, or you'll suffocate in the wheat. If we don't think about it too much, farming is a lot of fun. The rockets' red glare Nik lights a fuse the safe way. [July 1] I took my sons back to Pawnee Rock a year ago this week so they could relive my childhood. We went swimming, we drove down to Macksville, and we scrambled around in the yard where I used to play. The boys held their first toad and ate their first Dairy Queen cones. The highlight, however, was shooting off Black Cats. Fireworks are against the law in the forest where we live, so the boys had never gotten the chance to blow up anything. To be honest, I missed it a lot. We go to every fireworks show we can, but it's much more fun as a hands-on thing. We had flown into Denver and driven east on I-70. I couldn't wait -- I bought the boys a few boxes of snakes in Limon, 90 miles short of Kansas. As soon as we crossed the line at Kanorado, I loaded us down with Black Cats and punks bought in a tent in a field of wheat stubble. I figured it would be safest to introduce the boys to explosives at the river, so we unloaded hours later at the Dundee dam. In the company of a dozen other kids, my sons learned how to light the fuse, drop the punk, and run for safety. (We worked on not dropping the punk, but that'll take practice.) A couple of days later at the Rock, I found a few leftover firecrackers in the SUV and showed the boys the fine art of anthill excavation. Now, there was a summer activity they really liked. Perhaps the Black Cats will give the boys lifetime memories. Don't you remember your first firecrackers? Mine were ladyfingers, teeny bits of powder wrapped in red and green paper. The first year, Mom insisted on watching every explosion; the second year, I was on my own and I moved up to Black Cats. The Tutak and Keener boys had a thing for M-80s, so I got a next-door view of those, too. And every summer our cousins from Great Bend brought sacks of roman candles and whiz-bang fireworks out to our grandparents' farm, where we helped the nation celebrate. The summer after my senior year in high school, I helped a friend run a fireworks stand next to Rankin's butcher shop on the east edge of Larned. We made money hand over fist, and we felt free to take some of it out in trade -- bottle rockets. One hot, windless night after closing up, he and I and another pal shot a few dozen from the top of the Pawnee Rock pavilion. We set them up in glass Dr Pepper bottles, firing flights of three or four at the stars. When we tired of that, we shot them at one another. Nobody got hit hard; the misses streaked off toward town and exploded. So I have lots of Pawnee Rock fireworks memories, and now Sam and Nik have a few too. As I drove the boys down from the Rock, I stopped on the south side where the buffalo grass merges into the touch-me-nots and pointed to a flat place. "That, boys, is where one of the bottle rockets landed. It started a fire and we just happened to catch it before it burned up the Rock," I told them. My pals and I, embarrassed and scared that night 30 years earlier, stomped on the fire for a good five minutes. When we left, no blaze was ever deader. No psyches were ever more scarred. That's one bit of my childhood I hope my sons don't relive. On the other hand, I sure miss bottle rockets. August | July | June | May | April | March Copyright 2006 Leon Unruh |

Sell itAdvertise here to an audience that's already interested in Pawnee Rock: Or tell someone happy birthday. Advertise on PawneeRock.org. |

|

|