|

|

|

Search our site

Check these out    Do you have an entertaining or useful blog or personal website? If you'd like to see it listed here, send the URL to leon@pawneerock.org. AnnouncementsGive us your Pawnee Rock news, and we'll spread the word. |

Too Long in the WindWarning: The following contains opinions and ideas. Some memories may be accurate. -- Leon Unruh. Send comments to Leon October 2010The terrible thing

[October 29-31] Many of you know the old Schmidt home, just outside of town by the highway. It's a two-story frame house with a wide front porch and waist-high railing. The place has seen better days. It hasn't been painted in years and may never be painted again, but you can see spots where the last of the white hasn't flaked off. I was making the rounds during a visit to Pawnee Rock in the mid-1980s and stopped by late one October morning to see whether I could take some photos of the place without getting shot. I was let in off the hollow-sounding porch and offered a seat in the living room where the sun, coming from my left, slanted in through a window. My sitting on the couch raised a cloud of motes, which swirled in the light. It occurred to me that this faded home, with its papered walls and push-button light switches, had not had another guest for some time. Outside the window, a trumpet vine edged back and forth in the wind. Maybe against my better judgment, I accepted tea, which was served as a Nestea bag and hot water in a glass. "The house was built back in the 1920s," my host said. "It's a Sears house, picked out from a catalog and delivered in pieces. The Santa Fe dropped it off at the depot, and men with horse teams brought it to the property over a week's time. "Four families put up the house. There were the Rudigers, whose house it was, and Schmidts and two families of Schultzes. We all went to church together, and our grandparents had come over together. I was a Schultz back then. Just a child, fifteen. "Everybody had a job. My job was to apply plaster to the laths that made up the walls. The laths were run across the studs, and that's where people put insulation these days. I'd mix up enough plaster for a couple of hours and go along behind the men doing the carpentry. When they moved in, the Rudigers put up wallpaper. "There were women who made the meals for us. Mostly we ate fried chicken and bread and garden vegetables, but every couple of days they'd roast a pig or some chickens. They had a fire pit over in the side yard. . . . "Is your tea okay? Would you like more?" I shook my head. "I'm fine," I said. We sat for a few minutes, my host, as empty of color as the house, sizing me up. I realized that I hadn't seen any clocks nor sensed the hum of a refrigerator. "Did you ever hear about the terrible thing that happened here?" "No," I said. "Did someone die?" "Almost. There was a young fellow, Henry, who was sweet on one of the Rudiger daughters. He was a big boy with dark hair and eyes as blue as the sky. He was a farm boy, with strong hands. He'd show up for work before everyone else, and he'd be hammering away when they came up in their wagons. The sentences came out slowly, with a pause between them as if my host were paging through a photo album. "The girl? She was like springtime, as pretty and as . . . as lush as a Mennonite girl could be. Her name was Susan. Her hair was yellow and all the people in a whole room would turn their heads when she walked in. Her smile was so warm. "Oh, she was a delight. Lovely. "Well, Henry and Susan got along. She'd bring him his lunch, and afterward they'd walk around the property holding hands. "One morning when the men drove up, there wasn't any hammering, although Henry's horse was there. His dad found him unconscious on the second floor, and he was almost dead. His hand was cut off. "Which hand?" I said. "The right one. His working hand. The funny thing was, somebody had bandaged his stump. And his hand was missing." "Who would take a hand?" I said. "No one ever found it. Henry spent time in the hospital and came home with a hook. Susan married someone else. "Henry never understood his misfortune. He married a lesser woman the next year and found that he liked whiskey. Poor old Henry died out on the farm when he was just twenty-seven years old. His grave's up at the Mennonite cemetery. It's not much of a stone, but you can find it there." "That's a very sad story," I said. "It reminds me of when I was younger and I'd drive past this house and think there was a sad face in one of the windows. I never could see who it was. Is the house haunted?" My host sat without speaking. My tea, which I had barely sipped, was losing its heat even in the warm, still air. I set it on the floor next to my foot. Finally: "I bought the house about thirty years ago after Old Rudiger and his wife got hit by a truck when they were pulling onto the highway right out there. I've lived here a long time. "I was your face in the window. I still sit here, or I sit upstairs by the bed. I don't go out much. "The problem is that I can't sleep. For a while I even tried a little wine in the evenings, God save my soul, and the doctors in Great Bend gave me sleeping pills. Didn't help. "They think I'm too crazy and too old to save. So I just sit up in the bedroom at night, afraid." "Afraid?" I said. "Of what?" "Henry's hand." "I don't understand," I said. "I'm the one who cut off his hand." ". . . Go on," I said. "I was there early in that morning, even before Henry. I told him not to touch her again. I told him I was angry that he was in love with Susan. He refused to understand that I loved her more. "He brushed my arm away and turned his back on me. I picked up a hammer and hit him in the head with the flat side, and he fell like a sack of corn meal. I went down the stairs and got the hatchet from the fire pit and chopped off his hand. There was some twine, so I tied off his wrist and wrapped a cloth around it. "And then I left. I hid behind a shed in the next block until the other men showed up and found him. That's when I came over and looked horrified. "The doctors said that the blow on his head knocked out all of Henry's memory from that day. I guess that was my good fortune." "What happened to Henry's hand?" I said. "Well, I wrapped it in a rag and put it inside my jacket, and when nobody was watching I put the hand in the wall and plastered over it. There, behind where you're sitting." My back itched. I thought it would be impolite and maybe dangerous to turn and examine the wall. "Now," my host said, "I sit up at night waiting for the hand to come for me." I raised an eyebrow. "I see it in my dreams. Henry's hand gets out of the wall and climbs the stairs. It appears on my bed and its fingers touch my chin, like it's going to forgive me, and then it chokes me. I always wake up, but, Lord, I wish I wouldn't." My host's gaze drifted out the window. "Henry was a good man, and he deserved a better wife than me." She went quiet again. Her head drooped, and her breathing suggested that she had dozed off. A scratching -- so light at first that I mistook it for the trumpet vine rubbing against the window glass -- arose in the plaster behind me. I sat paralyzed, but a moment later my good senses hurried me into the yard. The screen door slammed behind me. Even in the midday sun I was cold and weak-kneed. I knew I should drive away, yet I turned and faced the house. The wind paused and the world stood still. From inside the home of old gray Mrs. Schmidt floated a rusty peal of laughter, and then there was silence. Park it here

The Pawnee Rock city park has playground equipment and a nice place where parents can sit and listen to the children and cicadas. [October 28] Back in the old days, when Shug was a pup -- that's how Grandma Unruh described long-ago time, and it didn't make sense to me then either -- we played on teeter-totters and swings at the school. It was nothing for us kids to ride our bikes to the west end of town in the evening, no matter our opinion of school itself. We didn't have a city playground. We had a lumberyard instead. Now, of course, the situation is reversed. The old Clutter-Lindas Lumber Yard is gone now these two decades, replaced partly by a metal fire station and partly by park space next to the tennis court. I'm pleased by the city park, a high-rent district development that I think shows real initiative by the city leaders at least a decade ago. There's a swingset and teeter-totters, plus park benches and whiskey-barrel planters under the elms. And the grounds are mowed. The tennis court still exists, fifty years after it was laid, but judging by the size of the net posts (no net was present in August) I'd say that the town's interest in tennis has been replaced by a desire for volleyball. And maybe volleyball is out as well; a skateboarding rail has been placed on the painted court. There's also a concrete mini basketball court, with real steel goals and chain nets. Someone should mow the court, though.

The Pawnee Rock tennis court has become a volleyball court and a skateboard area.

The Pawnee Rock basketball court in the city park awaits players on a summer evening. Sonny Knight, veteran and graduate[October 27] A couple of days ago, our notice that Sonny Knight had died included a question about his World War II service in the Navy and year of graduation from Pawnee Rock High School (1947). Virgil Smith, who graduated as the war in Europe ended in 1945, sent this note. Also, thanks again to Don Ross, who sent the photos in 2007:

In your pictures in section #42 ("They went to war"), there is a picture of Sonny with his mother, Wanda. He was pretty dapper in his Navy blues and whites with the bell-bottoms and was proud to serve. Coolidge: Short hop from Colorado

My through-the-windshield postcard from Coolidge, Kansas. [October 26] Follow U.S. Highway 50 far enough west and you'll come to Coolidge, the last whistlestop before the Colorado line. It's where the Arkansas River bed arrives in Kansas. Sometimes the river shows up, too. Coolidge is at the edge of the earth, the back of beyond, the hind end of nowhere. Our kind of place. Coolidge used to be a happening settlement, a cowboy haven called Trail City and, judging by contemporary reports, it was a rest stop on the bawdy highway to Hades. Now this Hamilton County hamlet on the Santa Fe Trail is more like our image of President Calvin Coolidge -- a withered, high-collared man with pursed lips. Thin lips. (It wasn't named for him, though, but for Thomas Jefferson Coolidge, a Santa Fe Railroad railroad president.) Coolidge, a mile from Colorado, has a grain elevator and a game-bird farm, and there's evidence of a once-upon-a-time football team. The pipe goalposts are in a pasture on the west side of town, not far from the old school, but anyone playing there these days risks ankle damage from stepping into a prairie dog burrow and falling on a prickly pear. Coolidge gets about 18 inches of rain a year, according to the state. I don't want to suggest that Coolidge has no charm. It's the kind of town where it would be pleasant to walk the streets in the morning and evening. Most of the houses are in good shape; it's just that there aren't many houses. The buildings made of limestone blocks are as substantial as ever. This roadside attraction caught my eye in 1983 when the movie "National Lampoon's Vacation" took Chevy Chase's family through here to visit Randy Quaid's home. The scenes weren't actually filmed in Coolidge, but they could have been. Pickups, wind, dust, dust in the wind. I drove around for half an hour and didn't see a soul. Still, it was one of my most-looked-forward to moments of my Kansas trip in August.

Downtown Coolidge, along U.S. 50.

This limestone building was erected in 1888.

The brick water tower rises on relatively high ground on the north side of Coolidge.

The Coolidge football field.

Gamebirds raised under this netting will be sold for hunting. Sonny Knight dies[October 25] Sonny Knight, born Darrell Dee Knight in 1925 in Garden City, died last Friday at the Veterans Administration Hospice in Wichita. He had graduated from Pawnee Rock High School and went on to the Navy and a career installing instruments in oil refineries.

His prepared obituary says he was in the Navy during World War II, although the PRHS yearbook includes him with the graduating class of 1947. (Can one of our readers solve this discrepancy for us? Did he serve and then return?) His parents were Harold Knight Sr. and Wanda Holmes Knight, and he spent much time with her mother, Maude Holmes of Pawnee Rock. One of his half-brothers, Harold Knight Jr., made himself famous in Kansas for broadly accusing elected officials of complicity in drug sales and racketeering. I met Sonny Knight once, a few years ago in Great Bend. He dropped in at the apartment I was visiting, and we chatted for a while about his life and distant times in Pawnee Rock. Mr. Knight, who was 85 years old, will be buried with military honors this afternoon in the Pawnee Rock Cemetery. (Full obituary)

Grave marker for Darrell (Sonny) Knight in the Pawnee Rock Cemetery. Books, books, books

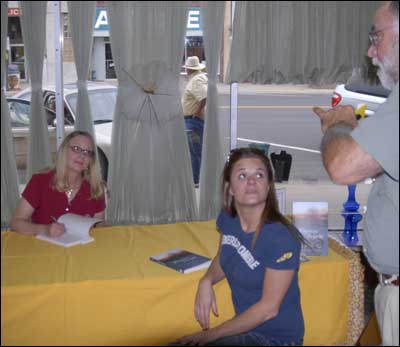

Cheryl Unruh autographs her book, Flyover People, for a reader at the Mystic Trove store in Larned. Jim Dye made this photo. [October 21] Readers living in the Pawnee Rock Metroplex have seen newspaper stories this past week in the Larned Tiller and Toiler and the Great Bend Tribune announcing that Cheryl Unruh would autograph copies of her book at a store in Larned yesterday. Local girl makes good. Cheryl wrote on her Facebook page that quite a few Pawnee Rockers, as well as many from out of our hometown, showed up at the Mystic Trove store. Jim Dye was there, and he took this photo of Cheryl and Glenn Mull (I don't know the other woman seated at the table). Every now and then a Pawnee Rock person makes a splash with a book featuring local color. Esther Deckert's stories about strong women comes to mind, and there was a citywide cookbook a number of years ago. We can't forget Roger Hanhardt's history of Pawnee Rock High School. I'd like to see more books on the singular subject we have in common -- Pawnee Rock family histories, essays, biographies, murder mysteries, cookbooks. To that end, I'm going to try my hand at writing a novel in November as part of National Novel Writing Month. The goal is to string at least 50,000 words together -- 1,667 a day on average -- and complete a first draft by November 30. My story will be set in a town much like Pawnee Rock. If it's any good, you might get to read it someday. If not, . . . well, I'm going to have fun trying. Fear of having to paint

When the green flag is out, copies of the Pawnee Rock News are available in the mailbox outside the post office. [October 21] In these hysterical times, one can easily imagine a great fear rising in the countryside that a city government is going to force homeowners to paint their houses. Don't worry, says the "News from the City of Pawnee Rock" section of the Pawnee Rock News published in mid-August. It won't happen here. "The City can NOT make anyone paint their house," says the article. "The City has been informed of someone going around and telling people this. The only thing the City asks if if you have any questions or concerns, please stop by the City Hall. "It is summer and there are lot of hot days. Let's keep the grass mowed and water puddles gone. City has been staying on top of mosquitoes this year." I imagine that city officials and staff run into this kind of concern week in and week out. I tip my cap to them. The white sparrow

[October 20] At one time, when I was new to Alaska, I felt blessed by natural visitors, as if the Good Fairy of Wildlife had tapped her wand on my shoulder. After 20 years, though, I've had enough animals in my yard that I can remain casual, but not quite bored, when a moose or fox strolls up close. But I have never seen a white sparrow. Now, that's unusual. Jim Dye has seen one. He found it at work. Jim, a machinist at Great Bend Industries at the airport, wrote that a coworker mentioned the sparrow. It took Jim some time, but he kept his eyes open and eventually the sparrow flitted into view. I didn't believe such a thing existed -- it had to be a different species, I thought -- so I Googled "white sparrow" and found that others have found them too. Congratulations, Jim. Your little friend is a real trophy.

I asked Jim where he took the photo, and he sent an image from a trip he made in a World War II-era Beech. A fortnight of Halloween, 1978[October 19] Now that Halloween is less than two weeks away, it seems like a good time to dredge up a scary memory from Pawnee Rock's past -- from late October 1978. A Great Bend Tribune story headlined "Vandals create 'mayhem' in small Golden Belt town' was written by reporter Maggie Lee. It begins: "Halloween mischief usually starts on Halloween. But Pawnee Rock residents have had to tolerate it the last two weeks. "Between 10 and 25 yound people have been creating 'general mayhem' in the 500-population town, Mayor Walter Myers said this morning. "'The idea seems to be to come to Pawnee Rock and raise hell," Myers said. 'Here's a general upheaval of law and order.'" Most of the mischief involved ceaseless dragging up and down Main Street, Myers said, but youths also stole furniture from a yard sale and burned it on Main. The story pointed out that not all the hoodlums were from Pawnee Rock -- they also came from Stafford and Pawnee counties. The story continues: "History is that Pawnee Rock is permissive, the mayor commented. And they made a game out of it, but now it's more than that, he added." Another Pawnee Rock resident said that during the October crime spree, tar was poured on the sidewalk in from of the post office and on a post office window, objects were dragged through the streets, and a toilet was set at the main intersection. Handrail over the big ditch

[October 18] There must have been a time -- maybe 80 or 90 years ago -- when this pipe handrail was straight. You recognize the pipe and the bridge. They cross the big ditch on Pawnee Rock's northern city limit. The bridge was erected back in the sepia-colored days when folks from town walked the quarter-mile to the Rock for a picnic or an evening's entertainment. Thousands upon thousands of hands have been laid on the polished pipe over the year to ensure safe passage. I'll wager that hundreds of little kids held on with both hands as they crossed the chasm. I was one of them. Who knows how many bike riders have posed near it, one foot on a pedal and the other on the pipe? As for the sit-and-talkers, I couldn't begin to estimate the number of butts that have swung over the edge, but it looks like enough of them have been applied to press a permanent depression into the pipe. Now the social value of the pipe is about gone. Only a crawling infant could use it for support now -- and I hope there are no parents in town who would point their infant up the concrete ramp and over to the other side. I grew up before video games arrived in town; the first one, Pong, came to the town bar in the mid-'70s, when I was in high school. Our homes received two or three TV stations, and they showed soap operas during the day and geezer-pleaser shows at night -- so we kids were still inclined to go outdoors. To fill our days, we played ball sports, went fishing, and rode bikes, and this bridge is where we hung out while plotting our adventures. I'm saddened to see the bridge in such worn shape. It's still a majestic structure in my memory. The Fall Gospel Sings is soon[October 15] The sixth annual Fall Gospel Sings Concert will be next weekend -- October 22 and 23 -- at Barton County Community College. Among the featured performers is Don Paden of Great Bend, who used to be the minister at the Christian Church in Pawnee Rock. Other performers are: 4-Told of Russell; Ed Huffman of Maize; The Torres Family of Haysville; The Toneys of Gallatin, Missouri; Praise to Him of Paris, Missouri; Joyful Noyz of Galesburg, Illinois; and McClellan Singing Sisters of Adams, Nebraska. The show -- put together by Lynn and Mary Chestnut, who have ties to Pawnee Rock -- is sponsored by eight churches. There's no admission fee, and an offering will be taken up to cover the performers' expenses. Pulled-pork sandwiches and other food will be available, and door prizes will be awarded. Showtimes are at 7 p.m. on Friday, October 22, and from 1 to 9 p.m. on Saturday. It's all at the Fine Arts auditorium. Mary Chestnut is my cousin, one of the daughters of Julietha (Unruh) Fox, who graduated from Pawnee Rock High School in 1942. When I visited her and Lynn at their home in Great Bend in August, she wanted to talk about the show. And she did, almost nonstop, for 20 minutes. It has been a long time since I've seen anyone so enthusiastic about a project. Her smile was infectious. She and Lynn simply love the singing and the idea that they can contribute the logistical expertise to make the concert happen. They're doing good work. Eaten up, eaten up

Book signing in Larned[October 14] Pawnee Rock native Cheryl Unruh, whose book, "Flyover People: Life on the Ground in a Rectangular State," is selling very well, thank you, will be in Larned next Thursday to sign copies.

Her essays in "Flyover People" include several set in Pawnee Rock, and the sensibility she developed in the Arkansas Valley can be heard in the voice of her writing. So, go see a local girl who is making good. Buy her book and ask her to sign it. And tell her that Leon sent you. Mystic Trove Book Boutique A window into another time

[October 13] I was browsing around city hall in August when I came to this room in the back of the old church. It was a space I had never been in before, having rarely been in the building when it was owned by the Methodists, and then mostly in the basement. It's a storage room now for ledgers, a metal detector, folding chairs, and boxes of records, but I suppose it had many other uses in its pre-secular life. It was a dressing room, perhaps, or a crying room for babes. Maybe Sunday school was taught there. The view out the wood-frame window was across several yards -- the back yard of the old parsonage, the lot where there used to be a house, and on to what used to be the Wilson home. I had seen this scenery a thousand times, although not from this vantage point. What struck me most was not the view, but the window and especially the half curtains. It's faded now, but you can imagine the gaiety that must have once been found in its stylized floral design. Leaves of bright green, petals of pink and yellow, printed on white fabric hemmed at the bottom and gathered at the top to accommodate the rod. Maybe it's from the 1960s, maybe the '70s. The cloth is practically sheer, and when the window was raised the curtains must have fluttered -- providing at least visual proof that the air was stirring. The city hall has its familiar touches -- wooden floor, altar, pews, kitchen, plaques, and coat rack -- but none of those things tells me "welcome" as gracefully as these old curtains. What I paid for a phone call

The pay phone stood just north of the highway, next to where the Vickers gas station was. The present grassy area then was sandy, and drivers often would pull up so they could talk without getting out. [October 12] Back in the dark ages of my youth, in 1971 or '72, I didn't want to make certain phone calls from home. Our phone, which was black and had a rotary dial, sat on a shelf between the kitchen and the living room, and any sense of privacy was purely imaginary. Had my parents overheard my calls, life would have been more awful than it already was. Mom would have been interested -- in what I now realize was a good way -- and Dad would have teased me. I was interested in neither response. I knew I was no good at talking to girls, but I wanted to figure out how to do it by myself, in the shadows. That's why I'd collect my pocketful of dimes and quarters after supper and head down to the pay phone at the gas station. It drove me crazy, there in the half-light, when the operator insisted on asking for the number I was calling from. It's your phone, I wanted to snarl, and the number is missing from the dial. Eventually, the operator and I would come to terms, and I'd push in my 65 cents or so to talk to a girl in Larned for three minutes. I'd grope around for the point of my call and ask for a movie date. I don't think my dates ever realized how much trouble it was to call them. There was no reason for me to expound on my shyness, so I made it sound like being called from a pay phone should be a great honor. In retrospect, I'd say that not one of the girls was fooled. The girls and I have been gone a long time now from high school. The highwayside gas station was torn down, and the Southwestern Bell phone is only a memory. I was going to add that using the pay phone is not a pleasant memory, but that's not entirely correct. I did stress out about calling and putting in the money before the calls were cut off, but the privacy -- and the girls' "yes, sure" -- was worth the effort. If nothing else, I succeeded on my own merits. The fact that I never had a steady girl in high school is certainly not the phone's fault. Good men at the fire

Joe Bilus and Shane Bowman take a hose to the fallen garage. Photo by Jim Dye. [October 12] Darcy Bowman wrote yesterday to give credit to two men who had helped fight the garage-and-house fire that occurred last week on Flora Avenue. In particular, she wanted proper identification for the men in a photo caption I had written to accompany a nice photo made by Jim Dye. Here's what Darcy wrote: "The two men that are in the number three photo of the fire on Flora street in Pawnee Rock are Joe Bilus and Shane Bowman, not the Mayor Timothy Parret which was not even in town that day. Please give credit to the ones that helped and were there like Joe and Shane who are not even on the fire department but offered a helping hand and then did not even get a thank you for their help." Thanks, Darcy. It is now fixed on the gallery page. The mistake was mine, not Jim's. I'd have to say that volunteer firefighters never get the recognition they deserve, and folks who step out of the crowd to help them should be recognized as well. What is this plant?

The seed pod, opened. [October 11] During one of my excursions through Barton County's gentle weedfields in August, I came across a plant that rang a bell -- but for the life of me I couldn't remember its name. Maybe I never knew it as anything other than "that plant with a ball inside a wrapper." My mom, Anita, suggested that it could be a Chinese lantern. The Kansas Wildflowers site backs that up, but it also seems like I should know it by another name, maybe one we had locally. I don't think I have ever heard the phrase "ground cherry," which the site also suggests. It was growing in a gully in a dryland field. Can anyone confirm that it's a Chinese lantern plant, or something else?

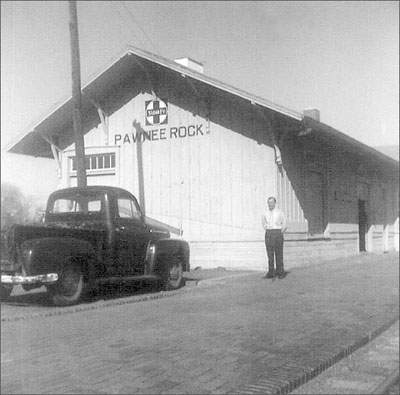

Max Blanding dies Max Blanding, outside the Pawnee Rock depot in 1963. Max Blanding, outside the Pawnee Rock depot in 1963.

[October 8] Max Blanding, who for several years was the Santa Fe station agent in Pawnee Rock, died this week in Wichita. He was 81 years old. Mr. Blanding and his family lived in town during the 1960s in the house on the northeast corner of the intersection of Bismark and Rock streets. The children, Joni and David, attended elementary school in town. Mr. Blanding was born in Formoso, a very small town east of Mankato in northern Kansas. He served in Korea during the Korean War. He is survived by his wife, Marylyn, to whom he was married for 56 years, as well as Joni and David. His inurnment will be in Florence. (Full obituary) (Thank you to Brenda Girard for passing along the news of his death.) Ghost towns[October 8] Amy Bickel, a fine reporter at the Hutch News, has begun a new series of feature stories about Kansas ghost towns -- the places that are not only dead but also nearly forgotten. Her story last Sunday says there are 6,000 dying or departed townsites in the state. She and a motorcyclist visited Chicago, which except for a schoolhouse is so gone from Sheridan County that it doesn't even appear on the Google map, and Google lists every forsaken whistlestop it can find. (Story is here) | (More turbines may be on the way)

Prairie Dog Town

The prairie dog, burrowing king of the high plains.

Where the bison roam, at Prairie Dog Town.

Rock doves, or pigeons, in their aviary.

Prairie Dog Town's barn.

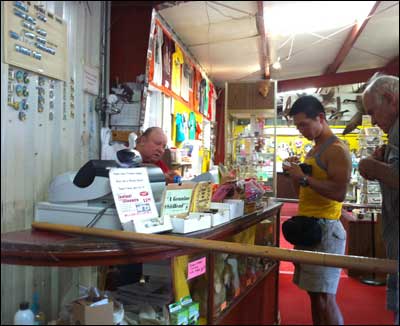

Rattlesnakes in a deep-enough wooden box. [October 7] The Prairie Dog Town and the World's Biggest Prairie Dog have been in Oakley for about four decades, almost as long as I've been driving through there on I-70. It's one of those oddball places that interstate highways attract -- and the odder the better. And, it seems, a free-range prairie dog farm, a petting zoo, and a six-legged steer is as weird as it gets in Kansas. At least, that's what draws the traffic on the long stretch between Hays and Limon. On my recent trip to Pawnee Rock (fly into Denver, drive a rental to Barton County), I gave in to my sense of adventure and finally stopped. Sure, I had that concern of all adults -- am I going to pay good money and get cheated? Would I feel dirty afterward for looking at freaks of nature? What the heck. It was a hot Friday afternoon and I had a week and a half of vacation ahead of me, and only 150 miles to go before Pawnee Rock.

Prairie Dog Town's welcoming door, where U.S. 83 comes up from Oakley to meet I-70.

Larry Farmer, owner of Prairie Dog Town. Larry Farmer, the cheerful man behind the counter, took my cash, lifted the gate, and began his spiel about what to look at and which doors to use. Start with the rattlesnakes, he said and pointed to his right. Wonder where they came from? The campground across the street, Mr. Farmer said. Well, there you have it. The Prairie Dog Farm is a true high plains operation. No imported killer snakes. The fenced yard behind the shop would be a black-footed ferret's idea of heaven, were such predators allowed on the grounds. There must have been two dozen mounds, most of them with prairie dogs. I was surprised that they weren't more acclimated to humans, but six feet was as close as I could get before they dived out of sight. I found myself assigning them human traits and personalities. The property's barn looks like a common wooden barn in a state moving toward metal outbuildings. Wooden shingles are missing, paint is chipping off, and the whole structure looks like a bad bet in a windstorm. It certainly adds to the ambience of being a day's drive from the Big City.

What all the hubbub is about -- the world's largest prairie dog.

On my lingering way out, I said hello to the bison, mouflon sheep, and animals you'd normally see in a zoo. The goats were frisky, hungry, and curious. The cattle were dull, and the pheasants walked back and forth. The foxes were doing it right -- dozing on their cinder-block box in a enclosure of the kind you'd find in many zoos. As I watched the pigeons flap around their cage, it occurred to me how many kids must grow up these days without ever having stood in a hayloft where the rafters are pigeon roosts. Back in the store, I wandered among the shelves and barrels of kitschy souvenirs and wished I were a kid again so I could beg my parents to buy me a spear or a pencil made from a twig or a bag of shiny rocks. Maybe this was the best part of my little adventure, harking back to the day years ago when our family visited such a store in Hays and opened my eyes to the world of toys one never saw in Pawnee Rock. I did the grownup thing, though, and left the cool stuff on the shelves. I bought a couple of postcards, waved goodbye to Larry, and set out for Hays. It occurred to me on down the highway that I had completely missed seeing the steer with the two extra legs.

Souvenirs.

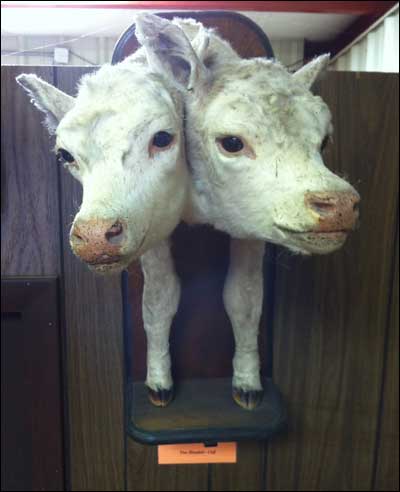

The two-headed calf. Is it cruel to keep a two-headed calf alive? Well, can it eat and walk around and do all the other things -- sleep and swat flies -- that a regular cow does? Then, I say, let it live and put a bow on its tail. What about you? Do you want to look at such "monstrosities," but you're afraid someone will see you? Are you afraid to give in to your curiosity because the act will reveal the banality in you? Yeah, me too. Let's imagine, however, that all of these "different" animals are examples of nature's attempt to find out what design works best. If a two-headed calf can drink more milk, grow faster, and multiply, nature has a place for it. If it can't do those things, it and those like it will die off. This is how nature works. Right now, four-legged, one-headed, short-haired, one-tailed dull-witted cows that moo and give milk and meat are in their heyday -- but in 2210 the climate might be so warm that cows with two heads are better suited for survival. If such cattle can grow faster and not gross out the customer, you know that the successors to Cargill and Archer Daniels Midland will pour billions of dollars into their development, and thus that variation of cattle will survive. Somewhere along the line, a genetic variation is going to catch hold. That's how I got my blue eyes and how you got so tall -- blue eyes worked better in northern climates and humans that walked more erect could hunt better, and early humans with those features survived more often in Europe and begat our progenitors. And here we are, the triumph of evolution so far. So, looking at these specimens of oddball flesh is really nothing more than watching species try to weasel their way into the future -- survival of the species. Throw out enough variations, and a certain little change eventually will make survival easier. I think that's something to celebrate. We're taught from an early age not to laugh at people who aren't like us, however we happen to be shaped or colored, and it's considered nearly as cruel to laugh at "deformed" animals. I think it is perfectly fine, however, to marvel at the variations that nature, as earnest as ever, tries out. We might be looking at the next link forward. Let's hear it for the firefighters

Pawnee Rock's truck kept the hoses full.

Larned's fire department sent a truck.

Albert sent a truck and water.

Great Bend's pumper pulls onto Flora Avenue.

Larned and Great Bend trucks were side by side. October 6] Let's hear it for the firefighters -- the volunteers and the paid crews -- who came to fight the fire Tuesday on Flora Avenue. Pawnee Rock's volunteers led the way, and they were supported by crews from Albert, Great Bend, and Larned. These photos, all by Jim Dye, show off the equipment. The son of a friend dies[October 4] Timothy Mix, the son of Larry and Carolyn Mix of St. John and the brother of Tina Weiszbrod of Pawnee Rock, died October 1 in Pratt. He graduated from St. John High in 1984, served in the Navy, and was the head cook at Pratt Community College. Mr. Mix will be buried in Fairview Park Cemetery in St. John. (Full obituary) Larry, a longtime supporter of PawneeRock.org, is a student of the history of the Santa Fe Trail. He frequently visits our hometown, and he and Carolyn participated in the parade in August. Seeking my midpoint, in Kinsley

[October 4] I'm not sure how I, as a young child, found out that Kinsley was halfway between New York and San Francisco. Perhaps my parents told me, or maybe it was in Ripley's Believe It or Not. It was before our country fell in love with the interstate highway system, way back when being along U.S. 50 and 56 meant more than watching cattle trucks growl past. Kinsley, of course, sits a couple of counties southwest of Pawnee Rock. In the brightly colored days of my Pawnee Rock childhood, I enjoyed figuring out how close Pawnee Rock was to the purported center of the national highway system. It's 34 miles to the park in Kinsley, which is 1,561 miles from San Francisco and New York. It should also be pointed out that although U.S. 50 does find San Francisco, its eastern terminus is not in New York City but in Ocean City, Maryland, and U.S. 56 ends in Kansas City. (Highway 50 and Highway 56) Furthermore, on other big highways north and south of Kinsley there are probably a half-dozen towns that are equidistant between the two coasts. Kinsley has made itself the most famous in that regard. Today, it seems to me that the exact spot of "halfway" was probably fudged. I suspect that the park was placed at the junction of 50 and 56 because land was cheap there and because, back in the day, more tourists could be lured off the highways and into town than if the true halfway spot were a couple of miles out of town. In my high school years, I passed the park a number of times on the way to gyms and football fields in the southwest. Usually I was in a school bus, and the park was just a glimpsed curiosity, a landmark I recognized the significance of but that (I felt certain) no one else understood. And yet I could be blissfully ignorant in Kinsley. In the evening of her life, my mom's widowed mother returned to Kinsley, her hometown, and lived in a small house. I drove to see her once, and on a gray afternoon we watched her beloved Arkansas Razorbacks football team play on television. She had many questions about my classes and future, and I think she was just glad to have my company. Surely I understood that we wouldn't have much time together, but I had places to go and so I got back on the highway. This past August, I again drove the 34 miles from Pawnee Rock, passing through Larned and Garfield in the rain and arriving in the Edwards County seat in time to catch the dripping end of the storm. I vaguely remembered the Midway sign. I didn't see it as I entered from the northeast and drove through what I thought was all of Kinsley. A clerk at the convenience store gave me directions, buttered with smugness, to the Dodge City end of town. And there was the park, tucked away beside the Santa Fe steam locomotive and the county sod house and farm-implement museum, which is itself snuggled into the long oval created by the looping overpass intersection of highways 50 and 56.

The sign -- which could be the most enduring claim to fame in the old railroad town, although I do enjoy Freedy Johnston's music -- has been worn by the weather, but it has been kept up. Seeing the sign was important to me not just because I was halfway between the two most interesting cities on opposing coasts, but also because the park was still there 45 years since I first stood in awe of its geographical significance. I was proving to myself that my memories were correct -- the wording of the sign, the park around it, the possibility that my sister and I really did scuttle among pieces of playground equipment, that we could have had a picnic with our parents. I think we all have a place like that, a vague childhood mind-story that must be reaffirmed. For me this time, it was a fading park in Kinsley. In the hearts and minds of other folks, the place might be Dodge City's Front Street, a sandy beach along the clear-running Arkansas River, or even the red cliffs of our own Pawnee Rock.

A second sign: A colorful sign shows the significance of Kinsley's location. Ralph Buller dies[October 1] Ralph Buller, who with his wife, Cleo, raised a busy family along the Correction Line west of Pawnee Rock, died September 29. He was 93 years old. He farmed, and his skin was burned red by the sun. He shared his good sense of humor -- not the backslapping kind, but the generous kind. He was approachable.

Cleo died in November 2001. Ralph is survived by two daughters -- Norma McGinnes of Council Grove and Karen Simonsen of Montana -- and eight sons -- Delbert and Thomas of Missouri, Joel of Arizona, Stanley and Timothy of Colorado, Daniel of New Mexico, Gordon of Wichita, and William of Larned. He had 22 grandchildren and 20 great-grandchildren. Mr. Buller's funeral will be at 2 p.m. Saturday at the Mennonite Church, and he will be be buried in the church cemetery. (Full obituary) |

Sell itAdvertise here to an audience that's already interested in Pawnee Rock: Or tell someone happy birthday. Advertise on PawneeRock.org.

|

|

|

I just wanted to give you some more info on Sonny Knight. He was in the class that graduated in 1944, but he joined the navy before the class graduated and when he got out, he decided he should get his diploma and went back to high school and finished.

I just wanted to give you some more info on Sonny Knight. He was in the class that graduated in 1944, but he joined the navy before the class graduated and when he got out, he decided he should get his diploma and went back to high school and finished.

He attended all 12 years of school in Pawnee Rock, and in high school was at times a member of the football team, annual staff, glee club, and for four years the mixed chorus.

He attended all 12 years of school in Pawnee Rock, and in high school was at times a member of the football team, annual staff, glee club, and for four years the mixed chorus.

[October 15] I rarely have much to add to the conversation about minor sports, but I'll throw in my congratulations to the K-State Wildcat football team for their bludgeoning of the Jayhawks last night. KU had control of the ball for more than half of the game and still lost 59-7. The sad thing about this school year is that K-State is apparently going to be hard to beat in basketball, too.

[October 15] I rarely have much to add to the conversation about minor sports, but I'll throw in my congratulations to the K-State Wildcat football team for their bludgeoning of the Jayhawks last night. KU had control of the ball for more than half of the game and still lost 59-7. The sad thing about this school year is that K-State is apparently going to be hard to beat in basketball, too. Cheryl has a literary connection to Larned. She checked out her earliest library books at the majestic old library and started her writing career at the Tiller and Toiler in the 1970s. I'm proud to say that she followed in my journalistic footsteps by recording the goings-on at Macksville High School (the Mustang Roundup) and then as a reporter/photographer at the paper in the days of editor Jack Zygmond.

Cheryl has a literary connection to Larned. She checked out her earliest library books at the majestic old library and started her writing career at the Tiller and Toiler in the 1970s. I'm proud to say that she followed in my journalistic footsteps by recording the goings-on at Macksville High School (the Mustang Roundup) and then as a reporter/photographer at the paper in the days of editor Jack Zygmond.

Electric noise: A couple of weeks ago I wrote about

Electric noise: A couple of weeks ago I wrote about

I wandered among the aviaries of pigeons and birds of higher interest and past the algae-rimmed pond to the shrine to the world's largest prairie dog and its pup. They're concrete. No one was available to photograph me, so I did it myself.

I wandered among the aviaries of pigeons and birds of higher interest and past the algae-rimmed pond to the shrine to the world's largest prairie dog and its pup. They're concrete. No one was available to photograph me, so I did it myself.

Mr. Buller's address was a Larned rural route and he was born in Goessel, but he and his family had strong connections to Pawnee Rock. They were members of the Bergthal Mennonite Church, and so the Bullers knew Pawnee Rock's families, and his kids were often our doorway to Larned's social life.

Mr. Buller's address was a Larned rural route and he was born in Goessel, but he and his family had strong connections to Pawnee Rock. They were members of the Bergthal Mennonite Church, and so the Bullers knew Pawnee Rock's families, and his kids were often our doorway to Larned's social life.